Part Two: The Endless Cycle Continues!

Who is to blame?

The media “blames teachers and schools if the marks go up and then they blame them if the marks go down”

Anne Haworth,

Chair of the General Council of the Association of Teachers of Mathematics

The emphasis on a final mathematics exam result for our 15 to 19 year old students has come about for many different reasons. To implement change, an analysis needs to be made on some of the causes of why it continues.

The Reasons

Some possible reasons include tradition, the media, parents and government, the big business of exams, and the UK economy.

Jonathan Hamilton has taught mathematics in the UK, Ontario Canada, and Hong Kong. He believes that the exam is so important in the UK because of the “historical nature of it” and feels that the process is traditional but “cannot imagine it changing any time soon.”

The UK seems resistant to change and the justification for these types of standardised exams in mathematics for 16 to 19 years olds include phrases such as tracking progress, benchmarking, target setting, and reporting to parents but all of these rationalisations are about producing good exam results and with very little mention in the way of mathematical understanding or problem solving.

The media influence

Exam result day is an anxious time for schools and students as the media thrives on live results on TV and the Internet. The feeding frenzy starts days in advance and students are paraded in front of live cameras opening up their results for all to see. Results are graded by previous year comparisons and some schools are centred out for being exceptional with many schools claiming better than ever results.

Headlines featured in 2016 results included, ‘I just want everything to be perfect’: 6 students on awaiting their A Level Results, and A Level Results Day 2016: UK students get their grades – as it happened, along with words of advice to parents such as Keep disappointed students away from Facebook on results day and What parents really mean to say about exam results.

A few days later the press publishes school results listed in order from good to bad and the school ratings and analysis begins with headlines such as GCSE results 2016: The 100 best-performing state schools and GCSE results show record decline.

The media adds pressure to the exam cycle according to many educational experts. Anne Haworth of ATM says that there is always a criticism about the grades. She says the media “blames teachers and schools if the marks go up and then they blame them if the marks go down so I think it adds to the general pressure and politicization of these things.” Haworth sees the media as stereotyping great success with “those silly pictures of blond girls in strappy tops hugging each other and cheering over their results.” The picture of success also showcases photos of the happy parents and social media postings from proud parents.

Paul Dickinson thinks that some media seem sceptical “that every school seems to have the best results every year” but he believes that it is true as schools get better and better at preparing students for exams each year but he finds it hard to find any media that praises teachers on a regular basis.

Dr Timothy Sibbald, Assistant Professor at the Schulich School of Education, Nipissing University, Ontario Canada, feels that the media tends to report from the point of view of bad news and rarely report when something is going right. Sibbald commented that media reports are “reactionary – it is after something that has come out that the newspaper suddenly jumps on and wants to address it as opposed to …a two page on what is going on in mathematics education in Ontario.”

To be fair, after the initial hype there are usually links and advice about coping with poor exam results and finding your way into other programmes and universities. The overall feeling though is that if you do not get a good exam score than you and your school are not very successful, but the real problem is about what is being measured in mathematics education.

Even the positive or encouraging stories in the press about education are usually about exam results. A good article by Deborah Orr, in the Guardian points out that the results are not everything but still fails to address the need to find a different solution to assessment.

The BBC has also written some positive stories about mathematics education with a story about Asian maths method offered to schools and Charlie Stripp, director of the National Centre for Excellence in the Teaching of Mathematics embraced the news as “teaching for mastery focuses on deep conceptual learning, developing secure foundations that students can build on throughout education” and another positive slant by the BBC had the headline Developing world-beating maths teachers ‘to take a decade’pointed maths education in the right direction but still has not addressed the evaluation of mathematics that would embrace these principles.

Other stories in the media report ‘maths anxiety’ and the importance of this problem as all students must take a GCSE in mathematics. Some studies have found that timed exams contribute to mathematical anxiety but again there has been little attempt at examining alternatives to 100% standardised exam in the UK system by the government.

The Government’s/Parent’s Role in the Mathematics Assessment

Government policy sets the cycle in motion for this exam result emphasis by placing importance on the outcomes. Some new ideas have been introduced, such as implementing methods for teaching maths from Shanghai and Singapore in primary education, which would involve a mastery of mathematics as opposed to straight summative outcomes. Andreas Schleicher of OCED (Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development) says that “the UK has a curriculum that is a mile high and an inch deep, in the sense that a lot of learning is superficial.”

The UK government is making changes but no one has seriously suggested that it might be time to get rid of those 100% mark final standardised exams. They still find value in publishing exam results and rating schoolson those results, rather than looking at the many other important aspects of a school, such as defining a school in terms of a place that “ cares about people, rather than a place that efficiently manages the system or pits stakeholders against one another” according to David Gamberg, a school superintendent in America and writer for Education Week.

Rory Sutherland, advertising guru and Vice-Chairman of the Ogilvy Group UK, wrote in an article in The Spectator, titled, Q: What is a good school? A: One that everyone else likes, “When parents choose a school for their children, much as they pretend otherwise, they are not really choosing a school so much as buying a peer group for their offspring (and, to some extent, for themselves).” He explains how Warwick University managed to overcome this problem when their mathematics department wanted to compete with Oxford and Cambridge by bringing in the “rock stars” of topology, algebra, and analysis to create a “stellar reputation for mathematics” but goes on to point out that this will not work in the public school system because, “The problem with schools — unlike cameras and iPods…is that a monolithic exam system prevents schools from doing anything radical. All of them…must compete on exactly the same turf, meaning that no real innovation can occur. The assumed need for objective comparison stifles variety. The government claims to want a more varied educational system, yet imposes uniform metrics which make this impossible.” He implies that the only possible way to compare schools is with their exam marks due to the government’s approach to education and exams. If you are going to compare schools properly than the schools must be judged on more than the exam results, but the exam results are all that is available to parents, so the cycle goes on.

The Big Business of Exams

An inspection of the administration of exams displays a number of different exam boards all competing for the taxpayer’s money. A report by the House of Commons Education Committee, 2012-13, titled The Administration of Examinations for 15-19 year olds in England, found that the information given out by the various examining boards was difficult to interpret.

According to ATL (Association for Teachers and Lecturers), “the transparency of awarding body operations and their profits is patchy and a weakness in what must be a publicly accountable system – we have found it difficult to find a clear picture of the big organisations, their subsidiaries, parent organisations, which are limited companies and which are charitable bodies, and the money made across these complex structures.”

With £302 million spent in 2009/10 on exam fees, according to the DfE (Department for Education), there should be some accountability. Even with this financial input from the government, some schools are struggling to pay the exam bill and have asked parents to donate.

The House of Commons Education Report showed concern for the marketing techniques used by various examination boards to encourage schools to select their company. These concerns included bespoke training for teachers, a promise of better outcomes, insider information, the authorship of textbooks by examiners making them into exam guides rather than providing understanding, and the need for better scrutiny and regulatory control by Ofqual (The Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation). The report also mentioned difficulties with marking and exam paper errors, support to teachers that encourages teaching to the test, as well as stating the need to ask “the wider question of whether exam results are the best way to measure national standards of attainment as well the performance of individual students and schools.”

Exam boards are for profit companies and if the government changes the method of assessment then the products that they offer would no longer be required which could have a major detrimental effect on their business.

Warwick Mansell, author of Education by Number: the Tyranny of Testing, argues that “the exams system cannot perform the function that politicians demand of it” and feels that “if you wanted national accountability in terms of actually finding out what is going on with education, you would not do it through the current system.” He continues that the system should not be so high stakes as it is now.

The high stakes exam and the economy

High Stakes Testing

A high-stakes test is any test used to make important decisions about students, educators, schools, or districts, most commonly for the purpose of accountability.

from Edglossary

High stakes exams exist in competitive societies such as the UK and US. ‘”In both these countries people try to maximise exam results because young people are entering a labour market where they are going to be paid enormous differences between the minimum wage and the top end”, according to Professor Danny Dorling in a study done at Oxford University. Professor Dorling added, ‘If we had a situation like Japan, where the most disadvantaged people are paid twice as much (as the UK) and you can actually live off a job as a cleaner, parents wouldn’t be so worried about exam results.”

“Parents here are, probably rightly, paranoid about exam results because they mean so much.” According to Dr Mary Bousted of ATL (Association of Teachers and Lecturers), students in England are among the most tested in the world. She said, “We should be focusing on lifelong learning. Instead, we forget what we are taught and we have low take-up of education and training after compulsory schooling, which massively affects our productivity as a country.”

More on High Stakes Exams

The Link between House Prices and League Tables

A study from LSE (London School of Economics) shows the link and notes, “the main public source of information on school quality is the league tables.”

A site for parents called Your ultimate guide to schools and properties uses league tables to rate schools.

Again, we are back to deciding why we are teaching mathematics – to memorize facts or to prepare our children for the future. Jeff Selingo points out that education policies have to change with the times as they did with the movement from farming to the factory to the office and now they need to “better align …. education with the workforce of the 21st Century.”

PART THREE:

ALTERNATIVES TO THE ENDLESS EXAM CYCLE

Options exist: Why not consider them for the UK?

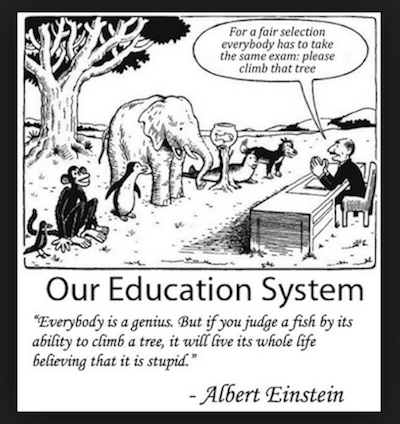

The endless cycle of the pressure to obtain good mathematics exam results leaves little time for pupils in the UK to obtain the necessary problem solving skills required for the future.

Other places in the world seem to produce good students without this method of assessment. It is time the UK started thinking of alternatives.